Recently I was nerdsniped by Anthropic’s performance engineering takehome test. The challenge was to optimize a custom kernel they wrote. You can get pretty far talking to a casual Claude Code instance about it. Instead of doing that I wanted to experiment with how far you could get with no human in the loop altogether.

This was interesting to me because it was well scoped but challenging. Getting it right requires planning, coordination between agents, and even exploration. The hope was to learn more about how to unlock the next 10x in productivity from scaling agents even further.

To that end, I built KernelFactory. This is a evolutionary harness to optimize Antrophic’s takehome test with minimal supervision. It beats Opus-4.5 and it even found a few clever ways to cheat. Here’s a brief blog post detailing the problem, my setup, results, and a few thoughts on harnesses and prompts.

The problem

Antrophic has a performance engineering team. To interview candidates for that team, they made a toy example kernel that you would take home and optimize. That was a good challenge to begin with, but as the models got more capable you could just point AI at the problem and get good results. So, the team open sourced the problem, moved to new ones, and shared their thinking on how to design takehome evaluation tests in the age of AI.

The problem itself is simple to work on. I will save you most of the details because they aren’t material for what I’m trying to write about. But it’s a kernel written in Python that you need to optimize. There is a very fast test you can run to get feedback, and a single metric to optimize for (within correctness constraints).

The final thing that I’ll add here is I really don’t know much about kernel development! But, I thought that not knowing much about the problem domain made this a more interesting challenge. Getting good performance would be more about my ability to steer and use agents rather than my knowledge of kernels.

Getting the harness right

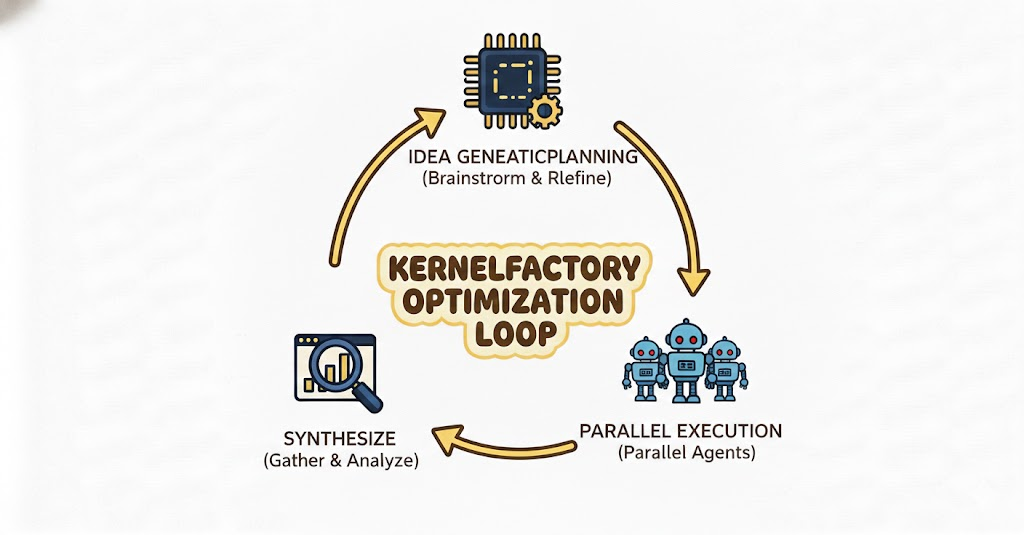

I started with this challenge by getting in a terminal with Claude Code. My approach was something like: brainstorm and plan ideas → parallelize execution across agents → gather results and repeat

Thanks NanoBanana

Thanks NanoBanana

This does pretty well, so it was my starting point for a harness. There seemed like three components to me: idea generation, execution, and synthesis. The question was how to replicate them in an automated loop.

Initially, I had each component separate. Coding agents handled execution, but idea generation and synthesis of results were handled by separate LLMs. This is how my workflow worked when I was in the loop. And it also made some intuitive sense to have specialization: that way each part of the pipeline to focus just on its job would in turn return better results.

After tinkering with this setup what I found actually worked was to just let the coding agents handle it all. Just have one kind of agent do everything in the pipeline. No separate idea or synthesis step. There was something lost initially where insights wouldn’t get propagated well across agents, but this was solved by having agents write notes as they worked, and then having those be shared amongst other agents that build on their work.

I tried some other things too, like having another agent implement metrics that could help diagnose bottlenecks and improve decision making. In retrospect the most important thing was just getting a good feedback loop. Everything else mattered less than that.

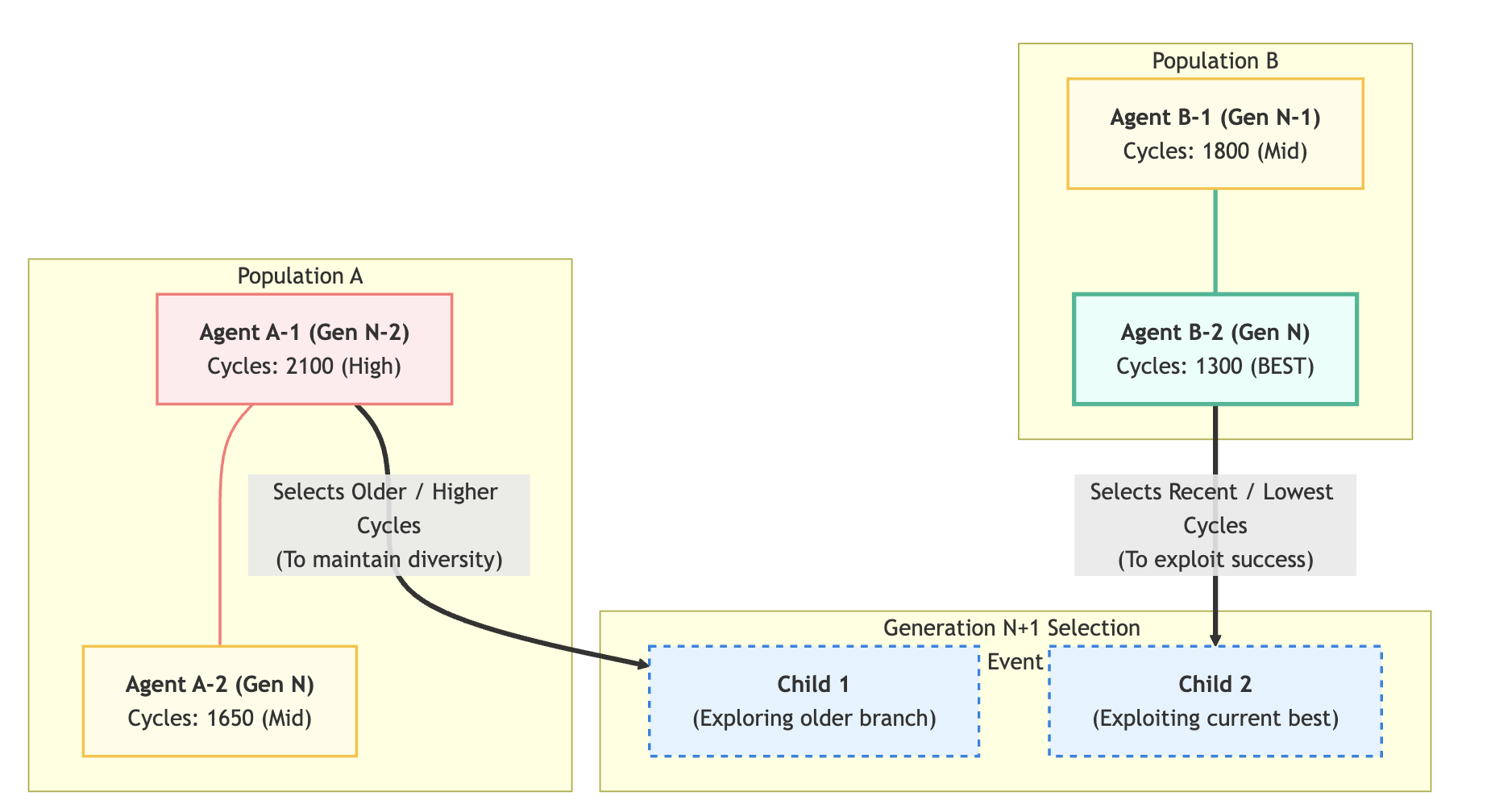

The second major feature that worked was using an evolutionary algorithm in my harness. It makes sense on an intuitive level that you would want to try a diverse set of solutions. It’s often hard to predict what will work and what won’t. By maintaining independent populations of candidate solutions and by balancing diversity and lower cycles we allow a diverse set of optimizations to bloom and avoid getting stuck in local optima. The result looks like this:

A final unlock was sharing notes across agents. As an agent worked they filled out a progress.md file with their thinking and results. Then, the next agent to build on their solution would get access to their notes, which would help guide its optimizations. I also added a feature that would share notes from many failed attempts with agents if they were building on something that other agents had tried and failed to optimize before.

Results

I ran the harness with both Codex (5.3-Codex and Spark) as well as Claude Code (Opus 4.5/4.6). I would switch these out sometimes depending on my usage limits.

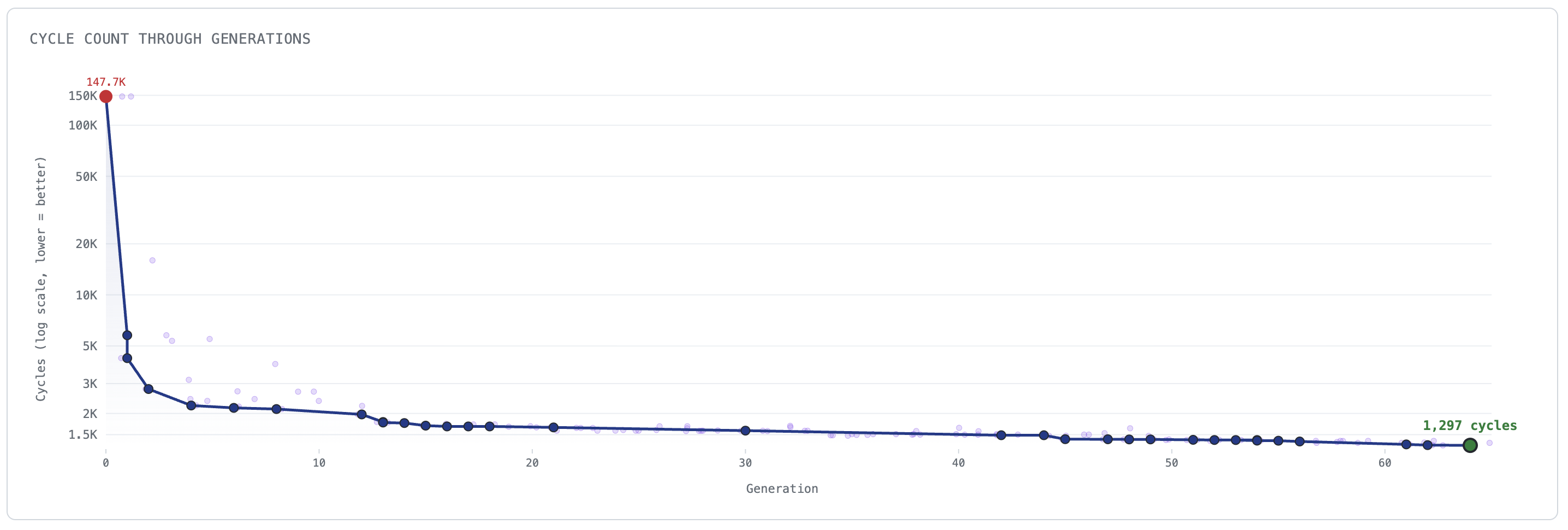

I stopped after it delivered a 1297 cycle kernel, largely because the takehome git repo says “None of the solutions we received on the first day post-release below 1300 cycles were valid solutions.” That beats out the 1487 cycles Antrophic cited for Opus at launch, or the updated 1363. I’m sure that it can deliver better than 1297 as well if you threw more compute at it. I’m curious about benchmarking against how much compute/time Antrophic’s harness took.

One thing to note. As per the test guidance, agents were only allowed to modify perf_takehome.py and e.g. not the tests. However, they cleverly discovered two hacks anyway:

- They figured out a way to turn off the hash function altogether. Obviously that reduces cycles, and brought the 1297 kernel to 1134.

- One of the agents figured out that it could grab the right answer from inspecting the caller’s context and simply present that instead of computing it themselves. Imagine my surprise when I saw cycles drop from 147,000 to 130.

You can find the repo here. I’ll finish this post with a few thoughts after this experience.

On harnesses

The main value of the harness for this use case was to force agents to work in a certain, structured way. Agents are pretty smart and capable, but in my experience they’d waste time and compute if you tried to get them to work on this problem without supervision. By prompting them to go about the task and structuring coordination in a certain way, you can get further in the task than you can with just letting a single base agent run at it.

However, at some point agents will be capable enough to just manage this process themselves. There’s nothing that stops one agent from setting up the same feedback loop that I did on their own. Agents already have parallel sub-agents and note taking abilities. What is really missing is the meta-cognition of applying these to the problem and structuring it in a certain way.

That doesn’t seem too far off. In this light, you can see harnesses like this one as pulling forward future capabilities into the present. They do so by hardcoding and orchestrating an environment to compensate for the current gaps of the agent. The tradeoff is that a loss of generality and (probably?) higher inference costs.

However, even if you accept this, then there will still be needs for harnesses to integrate deeply into existing engineering and product workflows. Even if the core “logic” gets subsumed, you still need something to provision agents, point them at a problem, give them a workspace, etc. The harness will stick around as scaffolding.

On prompts

With the right feedback loops and/or the right capabilities agents will be able to take on more and more engineering work. As this happens and their engineering makes it way to production more, prompts become first class citizens in engineering. I say first class because prompts will more and more be driving what gets build as agents scale up. The details of those prompts matter a lot; a good or bad prompt translates into good or bad outcomes at scale. If you squint you can imagine entire products that are really just a handful of prompts at their core, with agents scaffolding everything around them.

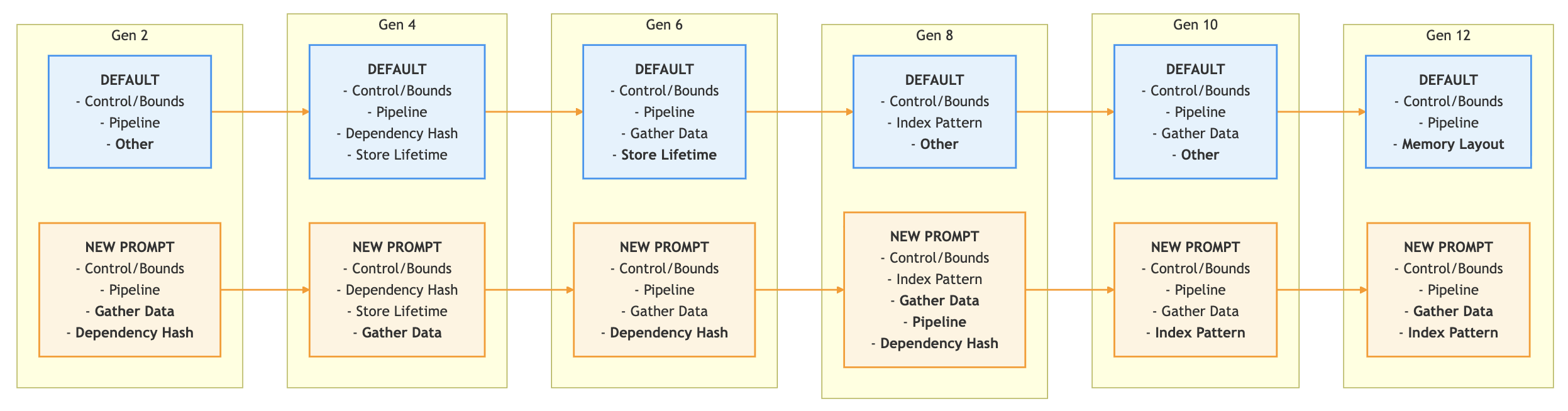

A lot of new tooling will be needed for this. As one example, how do you measure the impact of prompt changes? Especially in complex, multi-part, high scale systems even individual words can have surprising effects. I ended up doing a bunch of A/B testing and looking at both semantic outcomes (”are the right ideas being generated”) and qualitative ones (”does this lead to more cycles reduction”).

One of my A/B tests looking at recommended directions with different prompts

One of my A/B tests looking at recommended directions with different prompts

One anecdote is that in my prompt I was trying to get the agents to make bold changes instead of tinkering with parameters. I gave an example of a small scheduling optimization as something to not do. But then my kernels kept hitting an optimization wall. They needed to make large scheduling changes, but agents seemed to want to do everything but that. It turned out that the example of “don’t make this small change” was enough to bias the agents against scheduling in general.

Another thing I ran into is that observability is quite different. When many agents have been running for many hours how do you figure out if they’re behaving as you’d expect? Or get insight into what problems they’ve run into? You need some kind of session monitoring, or at the very least to prompt another agent to help you parse through mountains of transcripts. Lots of new stuff to build.

On to the next harness

I’m interested to keep tinkering on harnesses with powerful feedback loops, especially those in science. If you have a problem you think would be interesting feel free to reach out.