Anatomy of an MEV Strategy: Synthetix

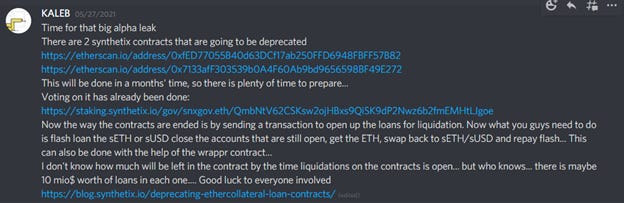

A few months ago notorious alpha leaker KALEB posted the following message in the Flashbots public searchers discord:

KALEB had previously leaked hundreds of thousands of dollars of alpha around changes to Synthetix. Sharing alpha in this den of bot operators was like throwing red meat at lions, and a quick look at the contracts confirmed there was a dizzying of money on the line.

Over the following weeks I planned and attempted to execute on a strategy to capture the MEV KALEB shared above. I am open sourcing the code I used for this, and I will walk you through my process and strategy in this post. You will not be able to run my code and print money, but this post will teach you how I think about designing new searchers and contains much alpha about doing so. Naturally this will be somewhat technical, but I strived to keep it understandable for a non-technical audience.

Step 1: Scope the opportunity

I'm not a Synthetix expert, so the first step was to learn what I was would be working with. Specifically:

I identified the relevant contracts

I read through their high level functionality on the Synthetix blog and searched for any documentation

I made sure to understand the governance change that was being implemented

I looked at the functions and identified those that seemed relevant

The summary of this stage of work was that Synthetix had trialed the usage of ETH as collateral for the minting of sUSD and sETH. You could deposit ETH in a contract and mint those assets so long as you were mindful that the value of your collateral didn't drop below a certain level relative to your loan.

However, after a ~ year the protocol had voted to end the trial. How could they do so when there were millions in outstanding loans still? Well, you could make ANY position liquidate-able. In effect after a long warning period the loans would go from being safe one block, to being liquidatable by anyone regardless of the value of their collateral! This would be triggered with a transaction from the "pDAO" address through the public mempool.

To liquidate a loan I needed to return the outstanding amount of the asset that had been borrowed (sUSD or sETH). In return I would receive the ETH collateral that had backed the loan I closed. As an incentive to liquidate these loans I would get back more value in collateral than I returned in sETH or sUSD. With millions of dollars in loans still existing at the time, this meant there was a lot of money to be made by liquidators. Furthermore, I would have to backrun the transaction from the pDAO contract so that I would take advantage of this opportunity as soon as possible.

Step 2: Understand the opportunity

Now I knew the basic mechanisms and had some functions I thought would be relevant. I then dug one level deeper into understanding precisely what functions I would call, what data I would need, and how to generate that data.

There were two functions I needed in production:

setLoanLiquidationOpen(): only callable by the contract owner (pDAO). Allows for liquidation of unclosed loans.

liquidateUnclosedLoan(): takes a loan ID and account address and liquidates that loan. Usable by anyone after setLoanLiquidationOpen() has been called.

Note that there were others, but I quickly discerned they weren't relevant. Now I needed to figure out how I would choose which loans to liquidate and how much sETH/sUSD I needed to do so. These functions gave me most of what I needed to get started:

openLoanIDsByAccount(): returns the IDs of all open loans associated with an account

getLoanInformation(): returns data about a loan given its ID and owner

However there were two catches. First these contracts would not tell you which addresses had outstanding loans, which was confusing to me. I found a workaround in a few minutes by downloading all of the transactions associated with the contracts on Etherscan and using Excel to create a list of unique accounts that had interacted with them. From there I set up the following pipeline:

Use getLoans to find out if that address had outstanding loans and if so record their loan ID

Use getLoanInformation to find out how much collateral was backing that loan, how much sUSD/sETH they had issued, and how much interest they had accrued on their loan

Sort by loan amount to surface the largest loans first and save a data structure to a json file

The second catch was that it wasn't immediately clear how much collateral you would get back for liquidating a loan. You could very roughly reason about it as a function of the outstanding loan, but I needed to be more precise. To do so I studied the code where loans were liquidated and understood exactly how the relevant numbers were generated.

All of the above data was data I could get or calculate on-chain. But doing so consumes gas. Given that I would be competing with others on the metric of how gas efficient my contract was, it was extremely important for me to move as much logic off-chain as possible to minimize gas usage.

After a few iterations I understood the minimal amount of data that I needed to get from the chain, this was a few variables about loans that I could then parse off-chain to inform what I input into my smart contract. However, the functions to get this information were complicated and querying all loans took longer than a block's worth of time. This was not tenable.

To get around this I wrote a short smart contract that batched together many requests for data and this led to an over 10x improvement of speed. Here is one of the functions:

You can see this used in my monitoring scripts here. Now I had a quick way to tell how much sETH/sUSD I needed, how much collateral I would get back for liquidating a loan, and thus how profitable the loan was.

Summary: This stage of work was about understanding the opportunity in depth and gathering all the data needed to execute on it in an efficient manner. Again, you need to do everything you can off-chain to lower your gas usage. The end result was two fast scripts for gathering the data I needed.

Step 3: Craft an execution contract

Flashloan strategy

You probably will need a specialized contract to extract MEV. I wrote a contract and test environment early on and used that environment to better understand the contract and make sure my data was right. This was mostly in parallel to steps 2 and 4.

I knew I needed to acquire millions of dollars in sUSD/sETH, so using flashloans would be necessary. Moreover, I would be burning these synthetic assets but getting ETH back. After some thought I realized that no matter what I would need to swap ETH for other assets regardless, but I could choose to do that before or after I liquidated positions. To illustrate here are two potential paths:

Option 1: Flashloan ETH -> swap for USDC -> swap for sUSD -> liquidate sUSD loan -> receive ETH -> pay back ETH flashloan

Option 2: Flashloan sUSD -> liquidate sUSD loan -> receive ETH -> swap for USDC -> swap for sUSD -> pay back sUSD flashloan

Given sUSD was only available on Aave and ETH was available on multiple flashloan providers, this was ultimately a choice about which flashloan provider I wanted to use. Ultimately I went with option 1 because dYdX had no fee, whereas Aave took one.

Gas optimization

You can find my full contract here, but this is the part after I received WETH from dYdX and proceeded to liquidate sUSD loans:

I spent a lot of time trying to minimize my gas usage. A lot of my design choices were informed by that. A few things to note here on the strategy of this contract

Instead of sending many performing individual liquidations and swaps, I opted to do many liquidations in one transaction, which amortized my fixedgas costs across those liquidations, and thus improved my bundle's competitiveness.

I needed to trade from ETH to USDC to sUSD in the best way and needed to decide to trade on Uniswap v3's with an exactInput or exactOutput function. No matter what I did I would incur some slippage somewhere, so I opted for exactOutput to avoid making a balanceOf call.

A tradeoff existed between precision across these trades and gas efficiency. There was little downside to a lack of precision so long as I managed to pay back my flashloan and because I was competing on gas efficiency I opted to optimize for that.

Some more tactical things to note:

Approvals for everything were frontloaded into the constructor of my contract. That way I could pay the cost for those at deployment and reduce my gas usage at the time of execution.

Instead of burning gas tokens from my account I burned gas tokens from my contract, again for gas efficiency.

Functions were named such that their selectors had leading 0s, which reduced my gas usage a bit.

Modifiers are slightly less gas efficient than adding require statements directly.

There are some more ways this contract could be optimized, e.g. using gas fees instead of coinbase transfers

0xSisyphus graciously offered to loan me ETH instead of me using flashloans - a big gas efficiency advantage. However over time many large loans returned their money, thus reducing the total opportunity. I decided against taking $ from Sisyphus because the opportunity was no longer large enough to justify doing so.

Summary: In this stage I created a smart contract to execute on the available MEV opportunity. Doing so optimally required thinking hard about the right strategy as well as how to minimize the gas used. This contract was developed iteratively and in parallel to my data efforts, and I made it in a test environment (Hardhat).

Step 4: Plan your execution

The economics of liquidation MEV and optimized gas prices

Armed with a well crafted contract and an in depth understanding of the opportunity, I needed to refine my strategy for how I'd execute on that opportunity. Recall that Flashbots' MEV-Geth client effectively runs an auction whereby the highest gas price bundle(s) win and are included on-chain. That important fact meant I needed to maximize the gas price of my bundle, not the total ETH I paid.

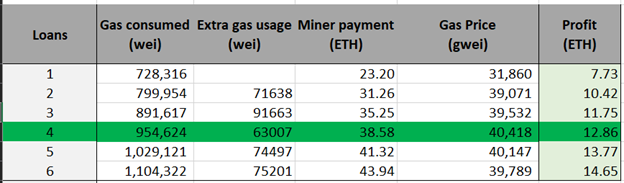

With this in mind and using the data I previously collected I made a spreadsheet to optimize my gas prices. My contract had both fixed gas costs and variable gas costs. The fixed gas costs were taking out the flashloan and making swaps. The variable gas costs were from the number of loans I wanted to liquidate. Intuitively I thought there would be some point where the marginal reward for liquidating a loan would no longer worth the gas cost. I ran several tests to derive actual numbers. These were my results:

Note the somewhat surprising result that liquidating only the top 4 (of 30!) sUSD loans was the most gas efficient thing to do. Every loan after this would yield more overall profit, but decrease my bundle's gas price and make it less competitive. If someone else tried to liquidate the top 10 sUSD loans all at once they would be almost 30% less gas efficient!

It also made most sense to only do sUSD loans instead of combining sUSD and sETH into one transaction given the outstanding sETH loans were smaller. Thus the potential rewards were smaller, and there was less money to pay to miners, which made them comparatively less gas efficient. I couldn't help but smile at these findings. If others were greedy and went for all loans at once, or lazy and liquidated positions individually, then I would win.

Still yet, the other loans were sitting there and were profitable to liquidate! Again, I tried to optimize for gas price, finding that if I liquidated the top 4 sUSD loans then it was most gas efficient to follow up by liquidating the next 6 largest sUSD loans together and separately from that the largest 2 sETH loans. Moreover, assuming that I won I could use my ETH profit from earlier bundles instead of flashloaning for more.

The Flashbots auction and my bundle ordering strategy

To repeat the situation: I was competing on gas efficiency, but I also wanted to maximize my profit by liquidating every loan. The optimal strategy was to submit a few liquidations per bundle in separate bundles. These would then be evaluated independently by the Flashbots auction. However, each bundle was dependent on the transaction from the pDAO making loans liquidate-able by anyone.

If the pDAO transaction was not in a bundle then the bundle would fail. But if I included the pDAO transaction in every bundle then only one bundle could succeed. After one bundle had landed all of the others would no longer be valid because they would attempt to mine the pDAO transaction a second time. Thus, I needed some way to only send the pDAO transaction in my first bundle, but ensure that the other bundles did not fail and get thrown away since they would not have the pDAO transaction.

The solution is a result of a nuance of the Flashbots auction. After searchers began to game the auction by lowering their miner payment post-bundle merging, Flashbots instituted two rounds of simulations.

First, all bundles are individually simulated to derive their gas price and check for failures. Second, successful bundles are ordered according to gas price, and resimulated in order to find conflicting bundles and ensure no bundles' gas price is lower than expected. Unless you were trying to do so you probably would never have a bundle where your gas price was lowered after merging.

I realized I could do the reverse of what the aforementing searchers did: instead of my bundles unexpectedly underpaying, they would overpay in the second round of simulation. To do so I would submit the first bundle with the pDAO transaction as expected, but to have an additional check on the remaining bundles. These bundles would infer which "round" of simulation they were in and change their execution accordingly. If they were in the "first" individual round they would not liquidate any loans - because they would fail if they tried - and pay the miner regardless in order to get a high gas price and pass the first simulation round.

Having passed the first simulation round, these bundles would be simulated in the second round behind the bundle with the pDAO transaction.

With this they could liquidate loans successfully. Moreover, these bundles would have a higher gas price than the auction expected, not a lower gas price, so changing execution here was not a problem.

How did I check for what "round" my bundle was in? By looking at the balance of my contract. If I had successfully liquidated loans earlier in the block (in a previous bundle) then my balance should have increased because of the profits I'd book from doing so. Thus, I added a condition to check for whether I had made any WETH profits, and if so, then proceed with liquidating loans. This succeeded in testing.

Summary: this stage was again about strategy. I used the data derived earlier as well as the contract and test environment to think about the economics of the MEV opportunity I was competing for and what the optimal strategy would be. Using actual data, I discovered a surprising dominant but difficult to execute strategy. Executing required a novel approach to bundle submission.

Step 5: Execution

With data, a contract, and a plan I could move to execution. Essentially I needed to craft bundles that would execute on my plan above and monitor the mempool for the relevant Synthetix transaction to backrun. Most of this is a matter of implementation at this point.

First, I used Blocknative to monitor the pDAO account for the relevant transactions. I had any transactions sent from the pDAO account streamed to my bot.

Second, in parallel I ran two monitoring scripts (one for both sETH & sUSD) to pull data from the chain, derive the optimal bundle strategy (e.g. liquidate the top 3 sETH loans first flashloaning X amount of ETH, do the same with next 2, etc), and produce the data my contract needed. I needed to run this every block in case prices changed or someone closed a loan and changed the optimal strategy. The results were saved locally.

Lastly, I had an execution script that would receive pending transactions streamed to my bot, load the optimal bundle strategy output from my monitoring scripts, craft the bundles themselves, and send them to Flashbots.

All that there was left to do was wait. During this time the largest sETH loans were repaid by the borrowers, so I shut down that part of the bot. A couple of the largest sUSD loans also closed, which significantly lowered the potential payout.

Step 6: The moment of truth arrives

Amusingly someone tried to bait bots into misfiring early by sending a transaction to the relevant contracts. I'm not sure if this worked on anyone's bots, but mine did not take the bait.

A few hours later the actual transaction was sent by the pDAO. After weeks of study and preparation this was the moment of truth. Everything went smoothly on my side: my monitoring scripts ran perfectly, the transaction was picked up, then bundles were created and submitted.

... and then disaster struck. No Flashbots blocks were mined for many blocks in a row. Not only did I lose the opportunity because of this, but no Flashbots searcher won it. Without Flashbots bundles at the top of the block to stop them an enterprising mempool bot stepped in and sniped all the profitable loans.

Regardless of having lost I think my approach was still the right one. My edge is in strategy and finding new opportunities, not participating in PGAs. So using Flashbots gave me the best chance of winning and given the widespread adoption of Flashbots it was incredibly unlucky that there was a streak non-Flashbots blocks.

MEV is sometimes made out to be the domain of shadowy super coders, but it doesn't have to be that way. It can be fun, interesting and stimulating. And the rules of the game - so to speak - are open if you look for them. This post was about my process for learning the rules of the game I was playing, developing a strategy given those rules, and finally executing on that strategy. Even though I lost I learned a lot and had fun along the way. I hope you did too, and that you join me in the next round

gg, mempool bot, you won this one. But I'll get the next one.